WHAT

Martin Winter

This text begins with a poem in Chinese. It is not very long, you can continue reading below.

我

我到底是什么人

怎么样的人

锅到底是什么人

怎么样的人

蜗牛到底

是什么人

怎么样的人

蝴蝶到底

是什么人

怎么样的人

蚂蚁到底

是什么人

怎么样的人

躺着到底

是什么人

怎么样的人

站着到底

是什么人

怎么样的人

爬着到底

是什么人

怎么样的人

我能不能

休息再说

明天再说

下周再说

等等再说

就稍微

等等

2024.6.22

I wrote a poem titled What in June 2024, when they had almost finished demolishing Shangyuan Art Museum in a village near Huairou outside of Beijing. I was there as a resident artist. Poetry is important at this place. Some of the founders of Shangyuan Art Museum were poets, including Cheng Xiaobei, the most prominent representative of the museum in China. I was invited for my poetry, this and last year. Mostly for poetry in Chinese. The poem What is 我 in Chinese. 我 doesn’t mean ‘what’, but the two words sound somewhat similar. The Chinese poem came first.

The poem is rather repetitive. Wo daodi shi shenme ren, zenmeyang the ren? This is the first two lines in the official Romanization for Mandarin Chinese. Romanization means using an equivalent to the characters in Latin letters, more or less. Letters of European languages with diacritical lines for the tones. There are four tones in Mandarin Chinese, plus the absence of a tone in some syllables. I am not using the diacritical marks here for now. ‘Wo’ in this poem is in the third tone. It is a little drawn out, so ‘wo’ sounds rather like ‘woah’. ‘Woah’, what is this?

Guo daodi shi shenme rén, zenmeyang de rén? I started to write ‘the’ in front of ‘rén’ just now. Rén means human or person. The tone in rén goes up, a bit like a question. Zenmeyang means ‘how is it’, it can be a greeting. The ‘z’ is not a voiced ‘s’, it’s rather like saying ‘tsih tsih’ when you imitate a bird or a cricket, a chirping sound. Tsen meh yang, three syllables. How, in what way, how is it, what kind of? The ‘of’ in ‘what kind of’ is ‘de’ in Chinese. Written d-e, but it sounds very similar to ‘the’, like in What the flower are you talking about?

Guo and ‘wo’ are both one-character words. Each character is one syllable in Chinese. Guo is pot. A pot for cooking, or a pan. A wok. Guo daodi shi shenme ren? Shenme is ‘what’. Daodi is something like ‘actually’, literally ‘at the bottom’ or ‘in the end’. Shi is pronounced without a vowel, or rather like ‘ugh’ after a ‘shsh’. Shi means ‘to be’, ‘is’. Pot actually is what person? What kind of person?

WHAT

What person

what kind of person

what kind of person

am I in the end

What person

what kind of person

what kind of person

is pot in the end

What person

what kind of person

what kind of person

is snail in the end

What person

what kind of person

what kind of person

is moth in the end

What person

what kind of person

what kind of person

is ant in the end

What person

what kind of person

what kind of person

lies down in the end

What person

what kind of person

what kind of person

stands up in the end

What person

what kind of person

what kind of person

crawls in the end

Can I please

take a rest first

Can I please

wait until tomorrow

Can I please

wait till next week

Can I please

just wait a little

Please can I

wait

MW June 23rd, 2024

There is a lot of repetition. Maybe that’s the main drawback. I just haven’t figured out how to make something with less repetition and the same effect otherwise.

What is this about? Why is this person asking these questions? Why the request for being allowed to wait in the end? What does it have to do with the demolition of the museum?

I am glad there is no obvious direct connection. No, there is no specific hidden explanation either, none that I am aware of. I wrote many poems at the time, one per day on average. They are all rather different. More realist, less strange. More directly connected to my reality. But I think there is a strong connection.

WOAH?

Das chinesische Gedicht war zuerst da.

维马丁 ist mein chinesischer Name. Weh Mahding, so klingt es ungefähr. Martin Winter auf Deutsch oder Englisch.

Alles andere geht so:

Wo 我

Wo daodi shi shenme ren

zenmeyang de ren

Guo 锅 daodi shi shenme ren

zenmeyang de ren

Woniu daodi

shi shenme ren

zenmeyang de ren

….

Auf Chinesisch ist jedes Zeichen eine Silbe. Zwischen den Wörtern in einem Satz gibt es Abstände, auf Deutsch oder auf Englisch etc., aber nicht auf Chinesisch, außer hier oben in der Umschrift. 我 wo bedeutet ‘ich’. 我到底是什么人, das ist die erste Zeile auf Chinesisch. 锅到底是什么人, das ist die dritte Zeile. Statt 我 ‘wo’ steht am Anfang 锅 ‘guo’.

Wo, oder eher ‘Woah’ von der Aussprache her, klingt ähnlich wie “guo”, oder auch “wok”, in der kantonesischen Aussprache. Ein Topf oder eine große hohle ostasiatische Pfanne. So ist das Gedicht entstanden, aus diesem Klang.

Woah, was ist das für ein Mensch,

was für eine Art?

Wok, was ist das für ein Mensch,

was für eine Art?

Woniu 蜗牛, oder ungefähr ‘Woahniuu’, ist eine Schnecke.

Woaniuu, was ist das für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Schnecke, was bist du für ein Mensch,

welche Art bist du?

Und so weiter!

Dann kommt auf Englisch “moth”, da ist auch dieses “o” oder “oah”. Nein, noch kein “sch” dazu… 🙂

Auf Chinesisch hab ich an diesem Punkt umgeschaltet. Hudie 蝴蝶, ungefähr ‘huuhdi-eh’, sind Schmetterlinge. Nichts mit ‘oah’, aber eben kleine Tiere wie Schnecken.

Chinesisch war zuerst da, Englisch auch schon am selben Tag.

Motte, was ist das für ein Mann,

welche Art von Mann?

Dann kommt die Ameise. Mayi 蚂蚁, ungefähr ‘maah-iih’.

Ameisen, was sind das für Menschen,

auf welche Art?

Nach der Ameise kommt schon ‘liegen’, oder im Liegen: Tangzhe 躺着, ungefähr tahng-dschöah.

Liegen, was sind das für Menschen, auf welche Art?

Nach liegen kommt stehen.

Stehen, das sind welche Menschen, auf welche Art?

Nach stehen kommt kriechen.

Kriechen, was sind das für Menschen, was für eine Art?

Kann ich mich bitte zuerst ausruhen?

Kann ich es bitte morgen sagen?

Oder nächste Woche?

Kann ich bitte ein bisschen warten,

ein bisschen

warten?

ICH

Was bin ich für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Was ist der Topf für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Was ist die Schnecke für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Was ist der Schmetterling für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Was ist die Ameise für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Im Liegen, was bin ich für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Im Stehen, was bin ich für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Im Kriechen, was bin ich für ein Mensch,

welche Art von Mensch?

Kann ich mich bitte zuerst ausruhen?

Kann ich es bitte morgen sagen?

Oder nächste Woche?

Kann ich ein bisschen warten,

bitte ein bisschen

warten?

MW 2024-6-22

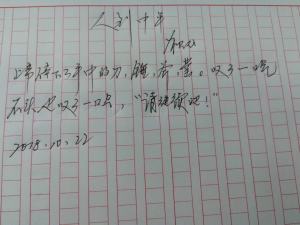

说

我觉得什么

都不想说

锅觉得什么

都不想说

蜗牛它什么

都不想说

蝴蝶也肯定

都不想说

蚂蚁她觉得

都不想说

躺着还觉得

都不想说

站着我觉得

都不想说

爬着也觉得

都不想说

蚂蚁它能

休息再说嘛

明天再说

下周再说

等等再说嘛

就稍微

等等

2024.10

SAY

I think I don’t

want to say anything.

The pot doesn’t want

to say anything.

A snail doesn’t want

to say anything.

A moth doesn’t want

to say anything.

The ants, they don’t want

to say anything.

Lying down I don’t

want to say anything.

Standing up I do not

want to say anything.

Crawling I don’t

want to say anything.

Maybe the ant

could take a break?

Wait until tomorrow?

Wait until next week?

Maybe just wait?

MW October 2024