Posts Tagged ‘fiction’

1月 12, 2021

Ezher

WENN

Könnte ich wählen,

hätt‘ ich ein Haus mit einem Holzzaun rundherum,

bisschen Boden anbauen, Hühner füttern.

An einem bedeckten Tag, wie ichs gern hab,

sie macht Esssen, ich mit einem Bruder,

wir liegen im Lehnstuhl, beim Schachspiel.

Könnte ich wählen,

wär‘ ich das Unkraut bei meiner Oma,

wär‘ eine Fliege,

aber nicht so lästig,

würd‘ mich verstecken in einer Ecke,

still auf den Tod warten.

Könnte ich wählen,

möchte ich nicht Ezher sein.

Ich wäre gern Rustem, Si Tunan aus „Renegade Immortal“

oder Zhou Yi aus demselben Roman.

Übersetzt von MW im Januar 2020

Ezher, geb. 1999 in Bortala, Xinjiang. Uighur. Schreibt seit 2019 Gedichte auf Chinesisch. Studiert in Beijing, liebt Musik. 《新诗典》小档案:艾孜哈尔,一九九九年生,维吾尔族,新疆博乐人。二零一九年尝试汉语写作,作品见于《白夜谭》《磨铁读诗会》。现在北京上学,喜欢听音乐。

Ezher, geb. 1999 in Bortala, Xinjiang. Uighur. Schreibt seit 2019 Gedichte auf Chinesisch. Studiert in Beijing, liebt Musik. 《新诗典》小档案:艾孜哈尔,一九九九年生,维吾尔族,新疆博乐人。二零一九年尝试汉语写作,作品见于《白夜谭》《磨铁读诗会》。现在北京上学,喜欢听音乐。

伊沙:与西娃、里所电聊:现在江湖上最蠢的就是在《新诗典》和磨铁读诗会之间还要私造对立自觉选边站的货,他们以为自己可以选择的生存空间很大吗?本诗作者刚在磨铁那边冒头,马上便将诗投过来,这便是聪明+健康人的正确作法,刚好我又很喜欢,认为作者在诗歌创作上大有前途。

况禹点评《新诗典》艾孜哈尔《如果》:人生有诸多愿景,人类有太多种愿景,不是每个都能实现,但如果你是个写作者,你可以把它们都写出来。

高歌:唯一认识的维族歌手是洪启,现在认识了第一位维族诗人艾孜哈尔,他却不想做维族人吗?末节够沉重,也许是周知的原因。2020年我想要一座磨铁的小猫人,未遂,新的一年继续努力,哈哈哈……

黎雪梅读《新世纪诗典》之艾孜哈尔《如果》:人们总是对现实的世界有太多的不满,为了达到某种心理平衡,就会产生各种各样不切实际的“如果”,以这些假设来弥补心中的缺憾。如果真的可以重新选择,人生也许会如诗中所写,少一些遗憾,多一些幸福。只可惜人生没有彩排,每天都是现场直播;人生也没有如果,只有结果和后果。因为命运无法假设。既然无法选择,那么只有面对现实,过好当下,以避免产生更多的遗憾,才是明智的选择。不管是怎样的人生,只要自己尽了最大的努力,就该无怨无悔,就无需“如果”,曾经的和以后的都没有“假设”。

马金山|读艾孜哈尔的诗《如果》的十一条:

1、每一首诗,都是诗人的内心,还是灵魂流泻出来的光,一股神秘的力量之光;

2、诗是灵魂的种子,发不发芽,开不开花,结不结果,都是诗自己的事情;

3、艾孜哈尔,1999年生,维吾尔族,新疆博乐人。2019年尝试汉语写作,作品见于《白夜谭》《磨铁读诗会》。现在北京上学;

4、对此诗人不甚了解,只有在磨铁读诗会读到其诗数首,纯净而幽远,直接且新鲜,切中生活的深层意趣,弥漫出广阔的视角和掷地有声的力量感;

5、回到本诗,三节十六行,以抒写内心的情感为中心,由三个排比句,道出了生活本质与要义,也是“我”的态度和想法;

6、诗的第一节,亮出内心深处不同的姿态,触及现实中的场景,细致入微而又不失质感,朴实无华且呈现出多样化的人物关系,深刻而清晰;

7、第二节,由两个角色的不同转换,背后却是透彻的思考与探索,复杂而又涉及生死,又一人生之命题;

8、最后一节,以“我”,和三个人,构成了一幅幅生动的画面,溢于字面,而又浸入思想的内部,平实而厚达;

9、诗的标题,以传统的笔触,无限的句法开头,以假定的方式,写下去;

10、本诗给予诗人的启示:“传统与现代有效的结合,并凸显出时代,也是一种视角和境界”;

11、祈愿之诗,心之所见。

标签:chess, chicken, choice, death, earth, Ezher, 艾孜哈尔, family, fantasy, fiction, fly, grandmother, grass, language, life, names, novel, NPC, people, planting, poetry, story, Uighurs, weeds, 新世纪詩典

发表在 2019, 2020, 2021, 20th century, 21st century, 磨铁, January 2021, July 2019, Middle Ages, NPC, poetry, Translations, Uncategorized, 新世纪诗典 | Leave a Comment »

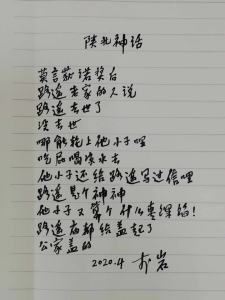

8月 28, 2020

Li Yan

MYTHEN AUS NORD-SHAANXI

Nachdem Mo Yan den Nobelpreis bekommen hat,

haben Leute in Lu Yaos Heimatort gesagt,

Lu Yao sei gestorben.

Gestorben?

Wie könnt er die Welt dem kleinen Kerl überlassen,

der müsste Fürze essen und kaltes Wasser trinken.

Der kleine Kerl hat noch Briefe an Lu Yao geschrieben.

Lu Yao ist ein Heiliger!

Was ist der kleine Kerl, eine Dattel-Teigfülllung?

Lu Yao hat einen Tempel, der ist schon gebaut!

Und zwar von der Regierung.

April 2020

Übersetzt von MW im August 2020

标签:attention, 莫言, 路遥, fame, fiction, history, Lü Yao, Li Yan, literature, memory, Mo Yan, myth, Nobel prize, novels, NPC, people, poetry, Shaanxi, stories, temple, writers, 新世纪詩典, 李岩

发表在 1960, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, 2012, 2020, 20th century, 21st century, April 2020, August 2020, Middle Ages, NPC, poetry, Translations, Uncategorized, 新世纪诗典 | Leave a Comment »

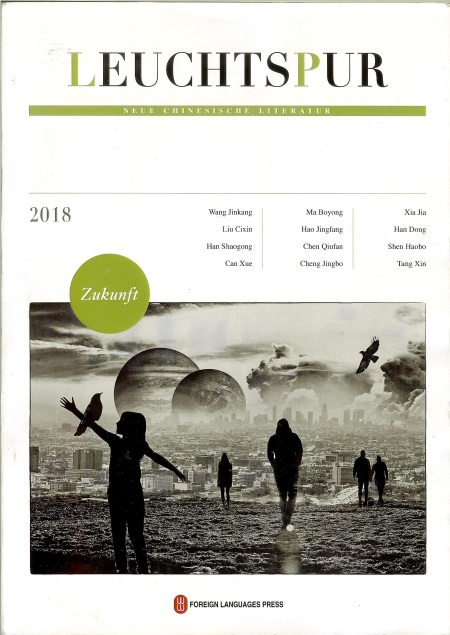

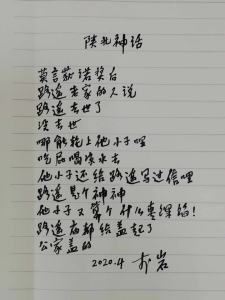

10月 27, 2018

erzählungen:

小说:

《贍養上帝》 刘慈欣 Liu Cixin: DEN HERRGOTT VERSORGEN, übersetzt von Martina Hasse

《深山疗养院》 郝景芳 Hao Jingfang: GEBIRGSSANATORIUM, übersetzt von Carsten Schäfer

《末日》 韩少功 Han Shaogong: UNTERGANG, übersetzt von Helmut Forster

《丽江的鱼儿们》 陈楸帆 Chen Qiufan: DIE FISCHE VON LIJIANG, übersetzt von Maja Linnemann

《影族》 残雪 Can Xue: SCHATTENVOLK, übersetzt von Martin Winter

《养蜂人》 王晋康 Wang Jinkang: DER IMKER, übersetzt von Marc Hermann

《草原动物园》 马伯庸 Ma Boyong: STEPPENZOO, übersetzt von Frank Meinshausen

《萤火虫之墓》 程婧波 Cheng Jingbo: GLÜHWÜRMCHENGRAB, übersetzt von Cornelia Travnicek

《热岛》 夏笳 Xia Jia: HEISSE INSEL, übersetzt von Julia Buddeberg

poesie:

詩歌:

韓東 詩歌 Han Dong: GEDICHTE übersetzt von Marc Hermann

沈浩波 詩歌 Shen Haobo: GEDICHTE übersetzt von Martin Winter

唐欣 詩歌 Tang Xin: GEDICHTE übersetzt von Martin Winter

erhältlich ab November 2018 in den Konfuzius-Instituten von Wien, Bremen und Frankfurt sowie bei www.FABRIKTRANSIT.net

unter “andere lieferbare Bücher”.

标签:age, animals, authors, bees, beijing, bicycles, care, china, Chinese literature, death, earth, family, fiction, fish, future, heat, heavens, high-speed, history, intergalactical travel, knowledge, life, literature, magic, memory, mountains, people, People's Literature, planets, poetry, religion, science, shadows, space, space ships, spaceflight, speed, stars, stories, translation, villages, war, world

发表在 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, 2018, 2081, 20th century, 21st century, Leuchtspur, November 2018, October 2018, poetry, PR, prose, Translations, Uncategorized, 人民文學 | Leave a Comment »

9月 22, 2017

Liu Xia

HYSTERISCHE REDE

ich bin die seele von einem mann namens nijinsky

ich esse sehr wenig obwohl ich dünn bin

ess nur was mein geist mich essen lässt

ich mag keinen angeschwollenen bauch

sonst kann ich nicht tanzen

ich hab angst vor den leuten

ich habe angst vor ihnen zu tanzen

sie wollen das tanzen zur unterhaltung

aber die unterhaltung ist tot

sie könnens nicht spüren

und wollen doch dass ich lebe wie sie

ich bleib lieber daheim

bleib weg von den leuten

schließ mich ein in die wohnung

schau auf die wände auf den plafond

ich kann auch leben wenn ich gefangen bin

ich bin ein philosoph ohne denken

auf der bühne des lebens

und keine fiktion

ich bin ein geist in einem körper

rede gern in gedichten

also bin ich der rhythmus

schlafmittel helfen mir nicht beim schlafen

alkohol auch nicht

ich werd immer müder

ich möchte gern aufhören

der geist lässt mich nicht

ich will geradeaus gehen

ganz hoch hinauf und runterschauen

die höhe spüren die ich erreichen kann

ich will gehen

2003

Übersetzt von MW im September 2017

癔语

我是尼金斯基身体里的灵魂

我吃得很少,尽管我很瘦

我只吃神让我吃的东西

我讨厌鼓胀的肠子

那会阻碍我跳舞

我害怕人群

害怕在他们面前跳舞

他们要我跳欢娱的舞蹈

欢娱就是死亡

他们感觉不到

却要我过和他们一样的生活

我要留在家里

避开人群

把自己关在房间里

望着天花板和墙壁

监禁中我也能找到生命

我是不思想的哲学家

是生命的剧场

不是虚构

我是有身体的神

喜欢用诗来谈话

我就是韵律

安眠药不能让我入睡

酒也不能

我越来越累

我想停下来

但神不允许

我要一直走

走到很高的地方往下俯视

感觉我所能到达的高度

我要走

2003

标签:alcohol, apartment, art, body, ceiling, crazy, dance, entertainment, fear, fiction, height, history, home, hysterics, imagination, Liu Xia, Liu Xiaobo, memory, people, philosophy, pleasure, poetry, politics, prison, rhythm, room, sleep, soul, spirit, 刘霞, 刘晓波, 劉霞, 劉曉波

发表在 1980s, 1989, 1990s, 2000s, 2003, Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

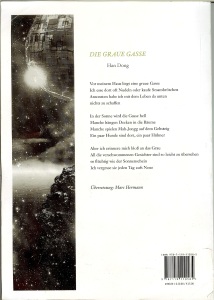

10月 6, 2015

Thursday, 8th of October 2015

Thursday, 8th of October 2015

20:00 h

First time in Austria!

»Human Life is Fiction.«

Liao Yiwu: Reading at Literaturhaus Vienna, Seidengasse #13, 7th district

Moderator: Wolfgang Popp (Author and Journalist)

Reading: PRISON. TEMPLE. (Long Poem)

Liao Yiwu (China) Mein Gefängnis. Mein Tempel.

erschienen in AKZENTE 3/2015, hg. v. Herta Müller,

deutsche Übersetzung von Martin Winter / 2015

Music: Liao Yiwu

Discussion

Wolfgang Popp and Liao Yiwu

Interpreter: Yeemei Guo

标签:austria, china, 維也納傅立特文學節, death, Erich Fried, facts, fiction, human, jail, Liao Yiwu, life, memory, monk, mountains, music, people, poetry, politics, prison, rights, temple, tibet, Vienna, witness, writing, 廖亦武

发表在 October 2015, poetry, Translations, Welcome! | Leave a Comment »

8月 31, 2014

Yi Sha

Yi Sha

CHINA DOWN AT THE BOTTOM

Pigtail is meeting his friend at the tent.

“Bao, do you have cigarettes?”

That box of cigarettes was stolen,

just like the type 64 handgun up on the roof.

Bao sits on the bed in the construction tent.

He broke his leg when they ran with the pistol.

Bao wants to sell it

and go to the hospital to get his leg fixed.

Pigtail is all against that.

“Bao, they will take down your head!”

Bao starts to cry,

crying harder and harder: “Look at the state I’m in!”

“I haven’t eaten at all for two days.

You want my leg to stay broken?”

Now Pigtail starts crying.

He’s wiping his face: “Look at this state we’re in!”

Pigtail decides to sell the gun.

He sells the gun to Mr. Dong.

This was the beginning of a big case:

The 12/1/97 murders* in Xi’an.

On such a night everyone thinks of the murders

I think of Pigtail and of Young Bao.

These hopeless kids from the bottom of China,

this people’s poet can’t get them out of his head.

1998-1999

Tr. MW, August 2014

*This serial murder case from the beginning of 1998 was made into a TV series and broad-casted all over China in 1999 and 2000. The police gun mentioned in the poem was lost on December 1st, 1997, and the case was eventually named after that date. The police in Xi’an were pressured to solve the murders before March 31st, 1998, because US-President Clinton was coming to Xi’an in June. See John Pomfret in the Washington Post.

(http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/WPcap/2000-01/13/086r-011300-idx.html)

伊沙

《中国底层》

辫子应约来到工棚

他说:“小保你有烟抽了?”

那盒烟也是偷来的

和棚顶上一把六四式手枪

小保在床上坐着

他的腿在干这件活儿逃跑时摔断了

小保想卖了那枪

然后去医院把自己的腿接上

辫子坚决不让

“小保,这可是要掉脑袋的!”

小保哭了

越哭越凶:“看我可怜的!”

他说:“我都两天没吃饭了

你忍心让我腿一直断着?”

辫子也哭了

他一抹眼泪:“看咱可怜的!”

辫子决定帮助小保卖枪

经他介绍把枪卖给一个姓董的

以上所述的是震惊全国的

西安12.1枪杀大案的开始

这样的夜晚别人都关心大案

我只关心辫子和小保

这些来自中国底层无望的孩子

让我这人民的诗人受不了

标签:fiction, film, guns, memory, murder, poetry, police, reality, TV, weapons, yi sha, youth

发表在 August 2014, Translations, Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

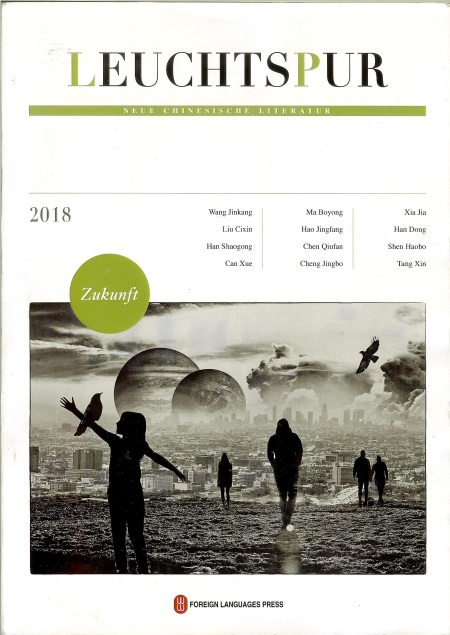

11月 3, 2012

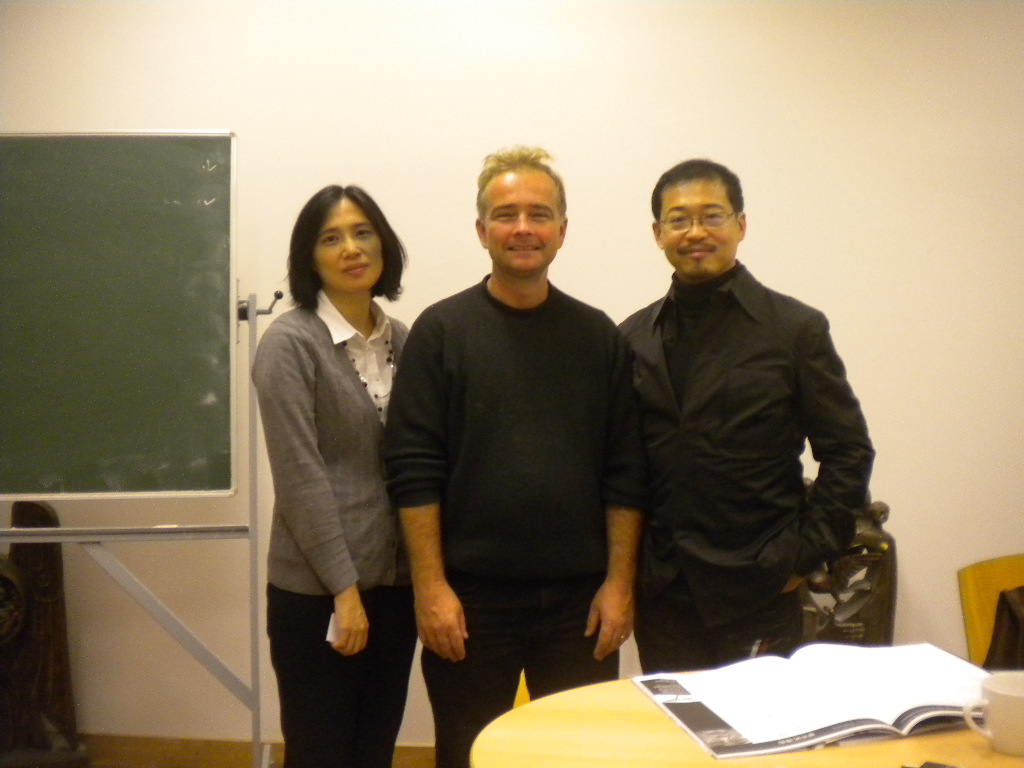

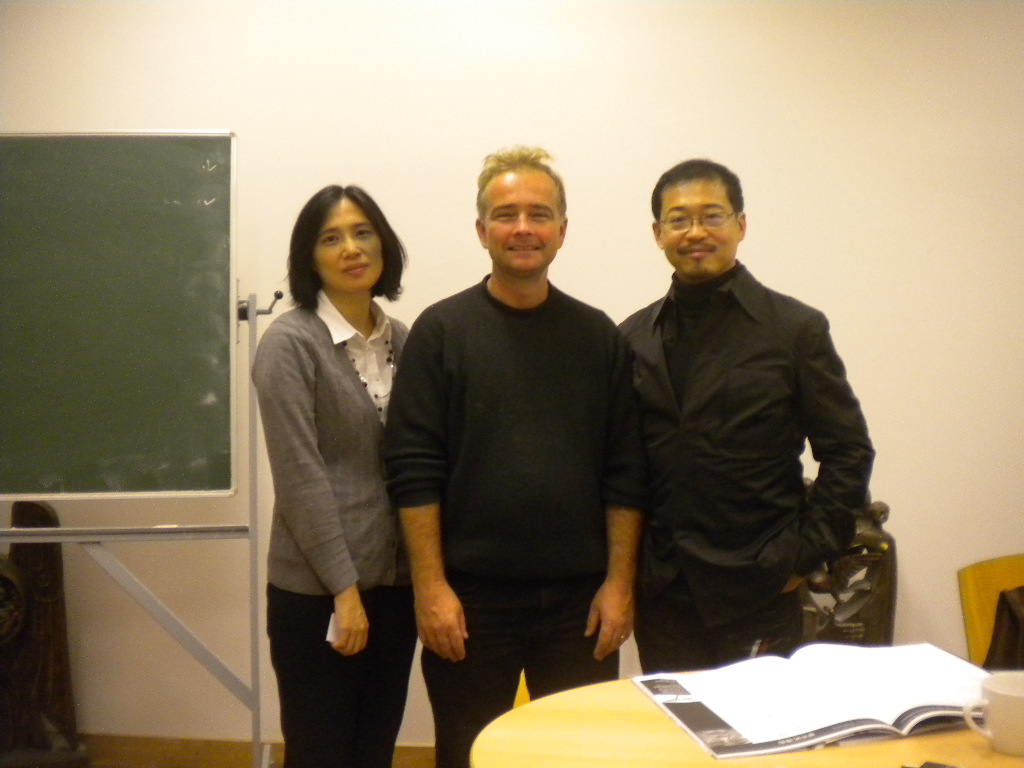

It was great. Lai Hsiangyin 賴香吟 read part of her story about a member of a former underground movement who has to confront his own weakness when his divorced wife needs his attention. I read Julia Buddeberg’s translation. Chen Kohua 陳克華 read three poems. First came Nothing 無, very Buddhist. Then a couple of last things. The last café 最後的咖啡館. The last motel 最後的汽車旅館. Very Taiwanese kind of motel dive. Secrete details, medical details, scientific details included in all three poems. Questions and answers. Audience members asked a few questions, and we had an interesting discussion. How and why did Ms. Lai write the story? What comes first, life or politics? And so on. Students, immigrants, veterans maybe, of Taiwan politics. Chinese Studies, East Asian Studies Institute, Vienna University 維也納大學東亞文化系. Austrian PEN. Two days in Vienna. Two nights. 維也納卌八小時左右。Arriving, getting lost on the airport. Translator’s fault. Translator’s idea, the whole thing. Not lucrative. I am sorry. Not smooth. Interesting, yes. Freezing. Exhausting. Fun. Fruitful, hopefully. Thanks very much! To the organizers. Thank you! Everyone who helped us. But above all 賴香吟、陳克華多謝!辛苦你們!Liebe. Liebe und Erinnerung. 愛和記憶。Love and memory. 賴香吟小說的主要題材。維也納很適合你們。柏林也是。柏林比較像現在的台北,相當開放、國際化的。柏林非常重視記憶。維也納的過去其實比柏林可怕,因為沒有柏林那麼公開的重視記憶。

So we had Q&A. Then the encore. We had Vienna in the café, in my translation. Apocalypse. Pouring coffee, to the last. Tabori. Hitler and Freud. Is there a Freud statue? There is his private clinic. Oh well. Statues of Strauss, Beethoven. Vivaldi, very recent. With his orphan students, all girls. Musicians, composers. When Aids broke out in Taiwan, the government forbade intercourse with foreigners. As well as doing it from behind. That’s how Chen Kohua thought of the poem. As a medical man. And risk group member. No intercourse with foreigners, no sex from behind, and we’ll be fine. Right. That’s where the quotation marks in the title come from. Freud and Jelinek. Dreams of Vienna. Love and memory.

陳克華

今生

我清楚看見你由前生向我走近

走入我的來世

再走入來世的來世

可是我只有現在。每當我

無夢地醒來

便擔心要永久地錯過

錯過你,啊–

我想走回到錯誤發生的那一瞬

將畫面停格

讓時間靜止:

你永遠是起身離去的姿勢。

我永遠伸手向你。

1985

Chen Kohua

DIESES LEBEN

Du näherst dich aus meinem früheren Leben.

Ich seh’ dich ganz klar, du gehst in meine Zukunft.

In die Zukunft der Zukunft.

Aber ich hab’ nur die Gegenwart. Wenn ich

traumlos aufwache,

hab’ ich jedesmal die Sorge,

dass ich dich verpasse, für immer —

Ich möchte zurück in den Augenblick des Fehlers,

den Film anhalten,

die Zeit und das Bild:

Für immer stehst du auf, um zu gehen.

Ich streck’ dabei die Arme aus.

1985

Übersetzt von Martin Winter im November 2012

标签:aids, austria, Chinese, contact, Elfriede Jelinek, 陳克華, 賴香吟, fiction, German, intercourse, life, literature, love, medicine, memory, poetry, politics, revolution, sex, Sigmund Freud, taiwan, translation, underground, Vienna, 國際交流

发表在 November 2012, October 2012, Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

10月 22, 2012

I want to thank Charles Laughlin for his recent posts on the MCLC list and on Facebook. His conclusion included these words: “Mo Yan’s critics are expecting the same of him that Mao Zedong would have: the political subservience of writers and their responsibility to serve as the political conscience of the nation”. Now I have written another blog post about this. 罗老师多谢!

Mo Yan’s 莫言 situation is ironic, as Charles Laughlin says. But serving “as the political conscience of the nation” is not the same as “political subservience”. It is rather the opposite. As we know, Murakami Haruki 村上春树 and his colleagues can be “the political conscience” of Japan, making “politically progressive gestures”, but Chinese writers in China, because of “political subservience” cannot be “the political conscience of the nation”, except obliquely in their fiction, poetry etc. Or in the first few days after they win a Nobel.

Along with Charles and many other people I am very glad that after Mo Yan was announced as a Nobel winner, he finally felt up to, or forced to open his mouth as a public intellectual, in contrast to the meaning of his pen name. Now he can be a public figure, like Murakami in Japan, not just an ambivalent functionary and a reclusive writer. Or can he? Is he going to say anything more on China-Japan relations or political prisoners? Is he going to mention Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波 in Stockholm? He will certainly be asked about other Chinese Nobel winners. That’s the nature of this particular prize, whether you like it or not.

Murakami and his colleagues can “serve” as public intellectuals, when their conscience tells them to do something additional to their writing. The irony is that under CCP 中国共产党 rule, there are no public intellectuals in China. There are occasional trouble-makers and commentators, like Ai Weiwei 艾未未 and Murong Xuecun 慕容雪村, Yu Hua 余华 and Wang Shuo 王朔. But can any of them speak their mind in public at length about Sino-Japanese relations or other sensitive topics? Apart from these writers and artists, there are professors like Cui Weiping 崔卫平, who issued the call to turn back to reason in Sino-Japanese relations, which got censored on Sina Weibo 新浪微波. She has often been prevented from traveling abroad. And there are some civil rights lawyers, who sometimes disappear.

Murakami and his colleagues can “serve as the political conscience” of Japanese society in and out of their books. Mo Yan has to be very circumspect with his topics. The Garlic Ballads was censored and supressed for a while. Mao’s “Talks” 讲话 at the “Yan’an Forum” 延安文艺座谈会 helped to make sure writers and artists could not speak their conscience. Vague documents like this have played an important role as instruments of obedience inforcement in one-party societies, as Anne Sytske Keijser and Maghiel van Crevel have shown in a recent article in “De Groene Amsterdammer” (10/17/2012). Mo Yan knows about this dilemma. His comments after he won the Nobel, and even some comments before, suggest he cannot find hand-copying and displaying Chairman quotes quite as harmless as Charles. That would be the difference between working with political realities in China and teaching about them in the US. The conditions of these political realities are still determined by largely the same factors as decades ago. As Keijser and Van Crevel put it, Mao’s “Talks” and other directives are up on the shelf, routinely mentioned in speeches by present leaders, and ready to be enforced again as needed. Yes, Mo Yan and his colleagues fought successfully for enough freedom to write great literature. Isn’t that enough? Not outside the realm of fiction, unfortunately. The cultural achievements of the 1980s couldn’t prevent the 1989 crackdown and everything that stays vague and threatening in theory and practice today.

Mo Yan writes “stupendous” novels, as Charles Laughlin says. Yes, he does. His development as a writer was influenced by the threat of starvation, the brutality in the name of revolution, and by the ideology. Yes, including the Yan’an “Talks”, as Charles shows. Now, Charles says, “China’s writers are receiving much-deserved international recognition simply because they are devoting their souls wholly to literary art.” Yes, they do. Liao Yiwu’s 廖亦武 speech in Frankfurt was in Sichuan dialect 四川方言. The text is available on the Internet. Try to find a video not dubbed into German. The German translation was fine, it just wasn’t dialect or even colloquial German. And it didn’t sound half as humble as Liao himself did. Politics made him into the writer, musician, poet and activist he is now. And his temper, his foolhardiness, as he readily admits. Not a hero, as Jonathan Stalling suggested. The German Book Trade’s Peace Prize has often been awarded to writers such as Orhan Pamuk.

The irony is that in theory, as taught by Charles, “Mao Zedong would have” reminded writers of their “responsibility to serve as the political conscience of the nation.” In practice, he silenced them. Virtually all, in time. So there would be no political conscience. That’s what Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four is about. Words like “Ministry of Truth” 真理部 are very well-known in China. 1984 is a vision of the closed world of a one-party state. Some moments of life in other societies can feel just as eerie, like a progressive college professor who turns into a cult leader, as in Murakami’s 1Q84, or, even more so, the perfectly cultured killer with secret roots in Korea. But on the whole, Japan in the 1980’s, evocatively and masterfully portrayed, is not ironic enough for connecting to Orwell’s 1984. I guess Taiwan under martial law 台灣戒嚴, in 1984, could have just made it.

Hu Ping 胡平, elected as independent candidate in Beijing’s Haidian district towards the end of the brief Beijing Spring over 30 years ago, recently circulated an excerpt from Mo’s “Life and Death Are Wearing me Out” (Shengsi pilao 生死疲勞). The novel was already well-known before the Nobel. A land owner who had his head blown off in the land reform in 1950 is born again as a farm animal several times, most famously as a donkey. In this excerpt, the donkey/landlord laments his unreasonable and unnecessarily bloody execution, until the guy who shot him tells him he acted with expressive backing from local and provincial authorities, to make sure the revolution was irreversible. So was it “a matter of historical necessity”? I don’t know what Hu Ping meant by circulating the email that somehow ended up forwarded in my inbox, because I don’t follow Chinese exile communications very closely. To me, the excerpt sounds just as absurd, evocative, tragic and yes, “stupendous”, as Mo Yan’s novels usually do. And thus rather close to Orwell’s 1984, or Wang Xiaobo’s 王小波 2015, in a way. I don’t think most readers would think that the author wants to commend, recommend or even excuse such acts of brutality.

There is another irony. Gao Xingjian 高行健 was awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 2000 even though, or maybe because, he did not and does not make himself available for political comments. Gao emigrated to France in the late 1980s and rescinded his Party membership in 1989, and it doesn’t seem he wants to come to terms with the powers that be in China in his lifetime. But on the whole, Gao has made about as many explicit political comments in the last 20 years as Yang Mu 楊木.

Chinese writing in 2012 is very complex. At least there is “much-deserved international recognition”, finally. Yu Hua’s essays “China In 10 Words” 《十個詞彙里的中國》 were serialized in the New York Times 紐約時報, among other international papers. And now Yang Mu, Mo Yan and Liao Yiwu appear together in headlines, also in the New York Times. What more could we wish for?

标签:china, culture, fiction, German Book Trade Peace prize, history, Japan, literature, memory, Newman prize, Nobel prize, politics, taiwan, theory

发表在 October 2012, Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

10月 19, 2012

标签:chinese language and literature, death, fiction, gender, history, hualien, literature, love, memory, poetry, reading, Tainan, Taipei, taiwan, translation, Vienna

发表在 October 2012, Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

Ezher, geb. 1999 in Bortala, Xinjiang. Uighur. Schreibt seit 2019 Gedichte auf Chinesisch. Studiert in Beijing, liebt Musik. 《新诗典》小档案:艾孜哈尔,一九九九年生,维吾尔族,新疆博乐人。二零一九年尝试汉语写作,作品见于《白夜谭》《磨铁读诗会》。现在北京上学,喜欢听音乐。

Ezher, geb. 1999 in Bortala, Xinjiang. Uighur. Schreibt seit 2019 Gedichte auf Chinesisch. Studiert in Beijing, liebt Musik. 《新诗典》小档案:艾孜哈尔,一九九九年生,维吾尔族,新疆博乐人。二零一九年尝试汉语写作,作品见于《白夜谭》《磨铁读诗会》。现在北京上学,喜欢听音乐。