Posts Tagged ‘horse’

12月 18, 2024

Zhang Wenkang

STRICK

Viele Menschen mögen Pferde,

ich auch.

Viele Menschen mögen Bäume,

ich auch.

Viele Menschen möchten ein Pferd

sanft und still an einem Baum.

Ich nicht.

Übersetzt von MW im Dezember 2024

磨铁诗歌奖·2023年度最佳诗歌100首|张文康《绳子》入选理由:张文康是哲学专业的,思辨能力很强,对诗的掌控力也很强。这首诗的结构非常巧妙,慢慢将读者带入诗人的思维之中,最后的“我不是”,是思维的断裂处,也是诗性的爆破处。题目是《绳子》,绳子作为一个隐藏的意象,把这首诗的诗性固定住了,绳子的另一端,被诗人紧紧握在手里。(磨铁读诗会 / 方妙红)

磨铁诗歌奖·2023年度最佳诗歌100首|张文康《冬日》入选理由:最后三行真漂亮,而且是突然出现如此漂亮的三行,令人先是猝不及防,继而击节叹赏。极其精彩的比喻,令整首诗骤然陡峭峻拔。这种突然感太重要了,如果只是精彩的比喻,而不够突然的话,就没有这么好的艺术效果了。年轻诗人张文康的意象能力令人印象深刻。这是一首可以让人想起瑞典诗人特朗斯特罗姆的诗。(磨铁读诗会/沈浩波)

磨铁诗歌奖·2023年度最佳诗歌100首|张执浩《不咏物》入选理由:一首以“不咏物”为题的带有古意、饱含真情的诗。当悲伤和喜悦都达到了顶点,文字传达的情感就全是自然流露,也无需托物言志了。诗人的语言张弛有度,节奏跟着语言一张一缩,仿佛能听到诗人紧张的心跳声。“先去把葬礼办好,然后 / 再去把婚礼办好”,最后两行掷地有声,诗人用最平实的语言托起了全诗的情感重量。(磨铁读诗会 / 方妙红)

磨铁诗歌奖·2023年度最佳诗歌100首|赵振成《未来战争》入选理由:个体到底属于哪个群体,赵振成并没有给出答案,却用这首诗唤起了我们的思考。身份政治的斗争在人类社会中从未平息,本诗步步推进,从国籍、大洲到星球,最后却因为所属街道的不同照样打了起来。飞扬、谐趣的想象中却又包含深思的隐喻,一首好诗同时也是一则寓言。(磨铁读诗会/胡啸岩)

Xiron Poetry Club

标签:allegiance, animals, country, 磨铁读诗会, death, earth, 赵振成, funeral, group, horse, horses, life, marriage, philosophy, quality, society, street, tree, trees, universe, war, Zhang Wenkang, Zhang Zhihao, Zhao Zhencheng, 张执浩, 张文康

发表在 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, 2020s, 20th century, 21st century, December 2024, Middle Ages, poetry, Translations, 沈浩波 | Leave a Comment »

12月 1, 2024

Mian Mian

AUSTERN

Die Frau sitzt zum Meer hin und sucht,

wo sie mit einem feinen Messer

hineinstechen kann.

.

Er sagt mir ins Ohr,

je härter die Schale,

desto köstlicher der Inhalt.

Die Frau schnippt mit leichter Hand

ein kleines Stück zartes Fleisch

ins Wasserbecken in der Sonne.

Er sagt leise zu mir,

das ist wie dein Herz.

Mein Herz

schwimmt mit vielen anderen

zuckend im Wasser,

der Schutz im tiefen Sand ist verloren.

Er fügt noch hinzu,

das kann man roh essen.

Übersetzt von MW am 30. November 2024

磨铁诗歌奖·2023年度最佳诗歌100首|面面《牡蛎》入选理由:面面的诗歌中总有一种深藏在平静中的锐利,一种手起刀落的锋芒,一股坚决确定的劲儿。她凭借激越又静谧的叙述风格,已经形成很强的个人作品识别度。这是一首太过独特的爱情诗,巧妙剖析和展示了爱的本质。这是一首很有镜头语言感的诗,妇人杀摘牡蛎肉的画面被处理得异常平静——阳光下的刺杀,伴随这画面交替出现的对话既日常又惊心动魄——玩笑背后的爱的较量和相互拥有。(磨铁读诗会/里所)

磨铁诗歌奖·2023年度最佳汉语诗歌100首|面面《一种平静》入选理由:好一句“相比寺庙/战火更应是佛像归处”,战火与佛像,这原本矛盾的事物,在面面强硬的诗句中,显示出了矛盾中的张力。不妨问一下,为什么战火更应是佛像归处?因为这是一种彻底的毁灭,毁灭中的美?不妨再问一下,为什么战火更应是佛像归处?因为那种毁灭后的平静,那种被摧毁的慈悲,让战火的残酷如在眼前。残酷与平静,战火与佛像,就这么静静地并置在一起。整首诗语言凝炼,准确,清晰,诗人没有再说任何多余的话,而埋在土中的佛头,正用它的半只眼睛看着我们。(磨铁读诗会/沈浩波)

磨铁诗歌奖·2023年度最佳诗歌100首|梅花驿《八吨煤》入选理由:既丰富,又纯粹,相当高级,当成为梅花驿的代表作,是口语诗最应该有的样子。也许这首诗可以倒过来读,当人们冬天在体委的游泳池游泳,或者窝在温暖如夏的家中,诗人的目光却由此穿透过去,看到平静美好的生活背后,有一口巨大的锅炉,看到锅炉旁边正在铲煤的人。诗人看得如此清晰,看到了他的动作和命运。“亲戚说你的力气就是证”,“他说没想到/自己有这么大的力气”,这样的语言真好,充满了口语的魅力。(磨铁读诗会/沈浩波)

磨铁诗歌奖·2023年度最佳诗歌100首|马亚坤《老马》入选理由:每次读到这首诗,磨铁读诗会编辑部里都会有人问,这是真的吗?真的会有这样的事吗?我认为是真的,诗人如此郑重地写下,此事一定是真的。真切地发生过,并且就是如此,草木灰上出现了一片凌乱的马蹄印,并且我愿意进一步相信,那位父亲,真的会转世成为一匹马。人类进入现代社会以来,更多地学会了怀疑,这很棒,但既要学会怀疑,也要学会相信。我们其实几乎不了解任何事物,每次有机会重新去看待事物时,都是世界对我们的馈赠。现在,当我们和诗人一起,看着草木灰上出现的马蹄印,就应该有和诗人同样的震撼。(磨铁读诗会/沈浩波)

Xiron Poetry Club

标签:animals, body, Buddha, 磨铁读诗会, damage, death, destruction, eye, eyes, 面面, 马亚坤, face, flesh, food, horse, knife, life, Ma Yakun, meat, Meihua Yi, Mian Mian, oysters, people, poetry, religion, sea, talk, taste, temple, war, 梅花驿

发表在 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, 2020s, 2023, 2024, 20th century, 21st century, Middle Ages, November 2024, poetry, Translations, 沈浩波 | Leave a Comment »

5月 5, 2024

Wang Fengfei

PFERD FÜR DIE SEELE

Opa hat den Geist aufgegeben.

Papa lässt mich am Tor

ein Papierpferd anzünden.

Meine Hand zittert,

erst beim dritten Mal brennt es.

Papa lässt mich rufen,

Opa steig aufs Pferd!

Ich rufe drei Mal,

Opa steig aufs Pferd!

Opa steig aufs Pferd!

Opa steig aufs Pferd!

Übersetzt von MW im Mai 2024

《接气马》

文:王凤飞

爷爷断气了

父亲让我把放在门口的纸马点燃

我手抖得不行

点了三次

纸马才被点燃

父亲让我喊

爷爷上马来

我照着喊了三次

爷爷上马来

爷爷上马来

爷爷上马来

李岩:陕北定边新诗典诗人王凤飞的一首诗,我初读有点惊异,凤飞诗有一种透彻的灵性,还有一种原生的超现实主义。

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/m2KSOwCYe1UArV3U4L8hYw

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/cZhiqISfY8wo1Fba_fejVQ

标签:death, family, ghost, grandfather, horse, soul, spirit, Wang Fengfei

发表在 1970s, 1979, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, 2020s, 2024, 20th century, 21st century, May 2024, Middle Ages, poetry, Translations | Leave a Comment »

8月 9, 2023

Ma Yakun

OLD HORSE

On the seventh day

she spread ash from wood and grass

at the gate

to see if father would leave a trace.

At one in the morning,

there really was a trace in the ash,

it was jumbled

imprints of hoofs.

She had never thought,

her father would come back as a horse.

She stood there alone,

hugging his portrait, and cried.

Under the pale moonlight,

everyone heard

“clip-clop, clip-clop”,

Old Horse running back and forth

out in the yard.

Shanghai, February 10, 2023

Translated by MW in August 2023

伊沙推荐语:

“好诗!这个世界如果全都是唯物主义者的天下,诗意至少死一半。在绵阳诗会上,马亚坤一曲古琴,太专业了,扫了众人才艺表演的兴。我觉得他在古琴上必然会有大成就,因为他是现代诗人。”

亚坤语:承蒙伊沙老师肯定和关注!当下古琴和诗,我都觉得没什么捷径可以走。对古琴来讲,只能远离当下生态,朝自己的内部和整体琴学深处孤独前进!不轻易立flag,但自当倾尽全力,争取证明您的预言!一切交给时间

徐江点评《新诗典》马亚坤《老马》:有神秘,有细节,所有这些又都指向了文学性。诗歌也只有在具备了文学性的前提下,叙事才是有效的。

水央评《新诗典》马亚坤《老马》

马亚坤,85后青年古琴家、诗人。荣获第十二届《新世纪诗典》年度大奖-NPC李白诗歌奖·评论奖;2019年上海市民诗歌节赛诗会一等奖!已出版诗集《古风操》。

这首《老马》在跨界诗人与诗会上就收获了一致的好评,正如伊沙推荐语精评“好诗!这个世界如果全都是唯物主义者的天下,诗意至少死一半。” 而我发现,亚坤的诗,虽然很多是“二手材料”(并不是自己的亲见亲历),难得的是却写得非常好,小说般的质感加上音乐人的听觉与节奏,令诗神采飞扬,高级而深刻!很佩服他这种从角度、选材、提炼、组合、升华的整合能力!他的诗评也很棒!智性理性深广度空间大,他的诗善于画龙点睛般地赋予诗魂,比如本诗,诗的最后,多绝妙啊“白色月光下/所有人都听到了/踢踏,踢踏/院子里老马/来回跑路的声音!”这样一种感性的神秘主义带出的“魔幻主义”色彩令本诗不仅活起来,并非同凡响!

亚坤文学功底深厚,又通晓古典音乐、有实力又有智慧,多面滋养而一通百通….如果哪一天他有空写小说,相信也会很成功!还希望能够读到一些他写自己或周遭的“一首材料”口语诗,相信也一样会很棒!

标签:afterlife, animals, ash, ashes, death, 马亚坤, horse, life, Ma Yakun, NPC, people, sound, tradition, 新世纪詩典

发表在 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, 2020s, 2023, 20th century, 21st century, August 2023, February 2023, Middle Ages, NPC, poetry, Translations, 新世纪诗典 | Leave a Comment »

2月 23, 2021

Jian Xi

ACKERGERÄT

Seine doppelten Lidfalten sind ganz viele geworden,

sein Blick ist sehr unklar.

Ich rufe ihn, er reagiert nicht,

wahrscheinlich ist er schon taub.

Er war ein Ackergerät,

hat den Pflug gezogen, folgsam wie ein Ochse;

hat den Wagen gezogen, die Hufe sind alle auf einmal geflogen.

Er hat auf Hochzeiten seine Rolle gespielt,

Bräutigam hoch zu Ross, die Braut in der Sänfte.

Am Kopf rote Seide, am Rumpf bunte Farben,

er hat viel beigetragen zur Freude.

Er war ein gemütliches Spielgerät,

in einer Ecke des großen Platzes.

Reiten für Kinder, jedesmal ein paar Runden

und ein paar Fotos, pro Kopf für zehn Yuan.

Jetzt kann er nicht einmal gehen,

sogar Gras frisst er nicht mehr.

„Pferdefleisch wird sauer, Gewürze dafür“

fällt mir auf einmal ein.

Ich streichle langsam durch seine Mähne,

er hebt nicht einmal den Kopf.

Übersetzt von MW im Februar 2021

Jian Xi, geb. in den 1970er Jahren, kommt aus Changzhi, Provinz Shanxi. Lehrerin, liebt Lyrik. 《新诗典》小档案:简兮,女,七零后,山西省长治人,教师,喜欢诗歌。

Jian Xi, geb. in den 1970er Jahren, kommt aus Changzhi, Provinz Shanxi. Lehrerin, liebt Lyrik. 《新诗典》小档案:简兮,女,七零后,山西省长治人,教师,喜欢诗歌。

伊沙:从昨日词的陌生化到今日物的陌生化。从80后三女将到70后女”新人”,《新诗典》的编排当获最佳剪辑奖。如何完成物的陌生化?本诗告诉你:将熟悉的事物拉开一定距离,再换一个角度去看它,你将获得新的收获。

Calligraphy by Huang Kaibing

况禹点评《新诗典》简兮《农具》:马离我们的生活已经太远了,曾几何时,它不止是牲口,还是伙伴。本诗还提到了一个人们遗忘的功能——农具。这种陌生化的发生,来自于社会的发展和演变。谈不上坏,也谈不上妙,我们人类只能接受它,带着不情愿和怅然。

Calligraphy by Huang Kaibing

黄开兵:初读简兮《农具》,以为是写牛,我从小放牛,对牛有感情,但一读到“像头黄牛”时就愣了,再读,哦,原来是写马!老马!越读越让人心痛。我抄的时候,只用笔尖,但很使劲,很缓慢,很沉地摧动着笔尖,力图以最细微的线条,写出那种钝痛。

Calligraphy by Huang Kaibing

标签:age, agriculture, animals, body, children, color, colors, 简兮, eyes, grass, history, horse, horses, instrument, Jian Xi, joy, life, meat, memory, NPC, people, picture, pictures, play, playing, riding, society, tools, wedding, 新世纪詩典

发表在 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, 2020, 2021, 20th century, 21st century, February 2021, January 2021, Middle Ages, NPC, poetry, Translations, 新世纪诗典 | Leave a Comment »

6月 27, 2018

Yi Sha

TANG DYNASTY HORSE

tang dynasty horse

fat

sturdy legs

big behind

tail like a whip

leaps into the sky

flies through the heavens

one long neigh

bloody neck

and no head

2017

Translated by MW in June 2018

Yi Sha

PFERD AIS DER TANG-ZEIT

pferd aus der tang-zeit

wohlgenährt

dicke beine

großer hintern

peitschenschwanz

steigt in die luft

fliegt durch den himmel

ein langes wiehern

blutiger hals

und kein kopf

Juni 2018

Übersetzt von MW im Juni 2018

唐朝的马|伊沙

唐朝的马

很肥

腿粗

屁股大

尾巴如鞭

腾空而起

天马行空

一声长嘶

血脖子

没有头

2017

标签:animals, art, behind, body, butt, expression, figure, head, heavens, history, horse, imagination, impression, improvisation, legs, memory, movement, poetry, sculpture, sky, sound, spirit, tail, Tang Dynasty, yi sha, 伊沙

发表在 1966, 2017, 2018, 20th century, 21st century, Antique times, June 2018, Middle Ages, poetry, Tang Dynasty, Translations, Uncategorized, Yi Sha, 伊沙 | Leave a Comment »

5月 11, 2018

Pang Qiongzhen

HORSE MUSEUM

horse sculpture

half out of its stable

but from up close it’s alive

imprisoned in a two square meter box

awkwardly craning

its living specimen head

the mane has been coloured

and made into pigtails

eight-hour shift each day

just like me

3/18/18

Tr. MW, May 2018

Pang Qiongzhen

PFERDEMUSEUM

eine pferdeskulptur

lugt aus dem stall

von nah ist es wirklich ein pferd

eingeschlossen in zwei quadratmeter bühne

bewegt es den lebenden

kopf den es darstellt

mit bunten zöpfen

acht stunden dienst

jeden tag

so wie ich

Übersetzt von MW im Mai 2018

标签:animals, expression, hair, horse, jail, life, movement, museum, NPC, Pang Qiongzhen, people, poetry, prison, speech, work, 庞琼珍, 新世纪詩典

发表在 2018, 20th century, 21st century, March 2018, May 2018, Middle Ages, NPC, poetry, Translations, Uncategorized, 新世纪诗典 | Leave a Comment »

11月 17, 2017

Yi Sha

KLEINER KLAPPSTUHL

nach der operation von meinem vater

schenk ich den klappstuhl zum warten

vor dem operationssaal

einem fremden stehenden angehörigen

so kommt es im Xijing-Spital in der nacht

auf den langen leeren gängen

zu einer verfolgungsjagd

ich renn mit dem rollbett von meinem vater

der fremde hinter mir

rennt mit zehn yuan in der hand

lieber fremder

lass mich ziehen

was ich irgendwem geben kann

in dieser stunde

ist halt nichts anders

November 2017

Übersetzt von MW im November 2017

《小马扎》

父亲的手术做完后

我把在手术室外

坐等的小马扎

送给了一个陌生人

站着等待的病人家属

于是在夜晚的西京医院

长长而空旷的走廊上

出现了雷人的一幕

我推着父亲的床跑

一个陌生人

在后面追我

手中高举着十块钱纸币

陌生人

快别追了

你就成全我吧

我能够给予别人的

也就是一只小马扎

2017/11

Yi Sha

TRAUM 1185

ich bin ein pferd

ein pferd das gern flieht

leute sagen sie fürchten

wenn ich wieder flieh

werd ich verrückt

aber ich glaub

flieh ich nicht

werd ich sterben

also muss ich weg

November 2017

Übersetzt von MW im November 2017

《梦(1185)》

我是一匹马

一匹爱逃跑的马

人们恐吓我说

如果再逃跑

我就会疯狂

我反倒认为

如果不逃跑

我就会死亡

所以还得跑

2017/11

LESUNG AM 1. DEZEMBER

MIT JULIANE ADLER UND MARTIN WINTER

Sovieso-Saal, Hackergasse 4, 1100 Wien

Freitag, 1. Dezember, 19:30

Eintritt frei!

标签:bed, books, chair, chase, corridor, dream, family, father, flight, folding chair, horse, hospital, poetry, reading, run, waiting, yi sha, 伊沙

发表在 2017, 20th century, 21st century, Antique times, November 2017, poetry, Translations, Uncategorized, Yi Sha, 伊沙 | Leave a Comment »

7月 19, 2017

Hung Hung

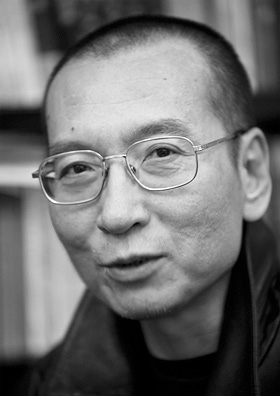

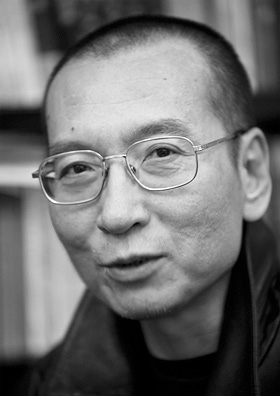

ONE MAN VS. ONE COUNTRY – FOR LIU XIAOBO

one man dies

one country awakes from a dream

actually it wasn’t sleeping

the country was just pretending to dream

it keeps its eyes open behind its mosquito net

watching who dares to dream their own dream

who dares in their dreams to sing their own song

who dares to call each stag a stag, each horse a horse

this country never sleeps

its atm’s count their money 24 hours

its warriors patrol on the net day and night

to bury alive every weathercock showing his head

this country infects with its disease

the livers that aren’t asleep

so they can’t detox anymore

they can’t tell the limbs to move around freely

the case history of this country is painted as poetry

everyone of the people it calls its citizens

must memorize and recite without rest

just like that hottest summer 28 years ago

a summer that seems to go on forever

one person dies

and the blood that was washed off

flows out steaming again on the square

to jump the dark floodgate

only when this sick country dies

every person can finally wake up alive

7/13/17

Translated by Martin Winter, July 2017

───────────────────────

Hung Hung

EIN MENSCH GEGEN EIN LAND — IN GEDENKEN AN LIU XIAOBO

Ein Mensch stirbt.

Ein Land erwacht aus einem Traum.

Eigentlich hat das Land gar nicht geschlafen.

Es hat nur so getan, als würde es träumen.

Hinter seinem Moskitonetz sperrt es die Augen auf:

Wer wagt es und träumt seinen eigenen Traum?

Wer wagts, singt im Traum sein eigenes Lied?

Wer nennt einen Hirsch einen Hirsch, und ein Pferd auch ein Pferd?

Dieses Land kann nicht schlafen.

Seine Bankomaten zählen sein Geld Tag und Nacht.

Seine Krieger patrouillieren 24 Stunden im Netz:

jeder Wetterhahn der seinen Kopf hebt

wird lebendig begraben.

Dieses Land steckt mit seiner Krankheit

jede Leber an, die nicht schläft:

sie können alle nicht länger entgiften

oder Glieder anstiften, sich frei zu rühren.

Es malt seine Krankengeschichte aus als Gedicht

und befiehlt allen jenen, die es seine Bürger nennt

das Gedicht vorzutragen bis sie nicht mehr können.

So wie in jenem heißesten Sommer vor 28 Jahren.

Der Sommer geht offenbar nie vorüber.

Ein Mensch ist gestorben:

Das abgewaschene Blut

spritzt wieder heiß hervor auf dem Platz,

schlägt gegen das finstere Schleusentor.

Nur wenn das schwerkranke Land endlich stirbt

kann jeder Mensch erst lebendig erwachen.

13. Juni 2017

Übersetzt von MW am 13. Juni 2017

──────────────────────

鴻鴻

〈一個人vs.一個國家──祭劉曉波〉

一個人死去

一個國家的夢醒了

.

其實國家沒有睡著

它只是在假裝作夢

它在蚊帳後睜大眼睛

看有誰膽敢作自己的夢

有誰膽敢在夢裡唱自己的歌

有誰膽敢指鹿為鹿、指馬為馬

.

國家沒有睡著

它的收銀機24小時還在數錢

它的戰士24小時在網路上四出偵騎

活埋那些冒出頭來的風信旗

.

國家把自己的病

傳染給那些不寐的肝臟

讓它們無法再排毒

無法再使喚四肢自由行動

國家還把自己的病歷彩繪為詩歌

要求所有被它指認為子民的人

汗流浹背地記誦

.

一如28年前那個炎熱無比的夏天

這個夏天也好像永遠不會結束

一個人死去

那些被洗淨的血

又熱滾滾從廣場上冒出

撲上黑暗的閘門

.

只有重病的國家死去

每一個人才能活著醒來

标签:1989, atm, blood, citizen, country, death, disease, dream, 鴻鴻, freedom, gate, history, horse, Hung Hung, life, Liu Xiaobo, liver, memory, Nobel Peace prize, poetry, prison, reality, song, square, stag, state, summer, 劉曉波

发表在 2008, 2010, 2017, 20th century, 21st century, poetry, Translations, Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

2月 25, 2016

Da Duo

FAMILY RITUAL

It has been a year.

I ask my mother

how father is doing over there.

Mother says my younger brother’s wife

has asked a wise woman,

who says father rides a yellow horse

to the market,

gets along with the neighbours,

he is content.

I ask her why

father went back to former times?

Didn’t we burn a paper car for him?

Mother says with a bitter smile,

“Maybe he can’t drive!”

Tr. MW, Febr. 2016

标签:burn, car, ceremony, Da Duo, death, family, horse, life, market, neighbours, religion, ritual, wise woman, yellow, 大朵, 新世纪诗典

发表在 February 2016, January 2016, NPC, poetry, Translations, Uncategorized, 新世纪诗典 | Leave a Comment »

3月 26, 2014

Hai Zi

BEIJING SPRING (FACE THE SEA, SPRING IN BLOOM)

from tomorrow, let me be happy

feed horses, chop wood, let me travel the world

from tomorrow, vegetables, grain

I have a house, face the sea, spring in bloom

from tomorrow, writing my family

tell everyone how I am happy

this lightning happiness tells me

what I will tell everyone

give every creek every peak a warm name

stranger, I want to bless you also

may your future be bright

may your lover become your family

may you find happiness in this world

I only want to face the sea, spring in bloom

1989

Tr. MW, 2014/3

Hai Zi

SCHAU INS MEER, FRÜHLING BLÜHT

ab morgen bin ich ein glücklicher mensch

hacke holz, füttere pferde, bereise die welt

ab morgen mag ich gemüse, getreide

ich hab ein haus, schau ins meer, frühling blüht

ab morgen schreibe ich allen verwandten

schreibe von warmem blitzendem glück

was dieser blitz mir jetzt gesagt hat

ich sag es jedem einzelnen menschen

geb jedem fluss, jedem berg warme namen

fremder, mögest auch du glücklich werden

ich wünsch’ dir eine leuchtende zukunft

aus deiner liebe werde familie

finde dein glück in diesem leben

ich will nur schauen ins meer, frühling blüht

Peking, März 1989

Übersetzt von MW im März 2014

标签:1989, beijing, blossoms, family, flowers, food, future, grain, Hai Zi, Haizi, happiness, horse, letters, names, poetry, sea, spring, travel, vegetables, warm, wishes, wood, work, 海子

发表在 March 2014, Translations, Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

1月 31, 2014

YAN LI! Yesterday I posted his THREE POEMS FROM THE 1980s. Prominent words and themes in GIVE IT BACK (1986), YOU (1987) and YOU (1989) are “love” and “citizen”. The most prominent news story from China in January 2014 was the trial and sentencing of XU ZHIYONG 许志永, a legal scholar and leading activist of the New Citizen movement. Trials, everything connected with rule of law has been very much in the news for a long time in China. See Han Zongbao’s poem 韩宗宝 from fall 2013, for example.

Xu’s statement in court was titled “FOR FREEDOM, JUSTICE AND LOVE“. I was rather surprised at “love” being evoked as a core political value like “freedom” and “justice”. Liberté, Egalité, Amour? Xu’s statement and the accompanying account of how authorities had tried to warn and intimidate him before he was arrested make it clear that he is not only an activist for the rights of migrant workers and for greater openness about public servants’ financial assets. “Can you explain what you mean by Socialism?”, he asks. This is certainly a very important question. China is a Socialist country, at least by name, just like Vietnam, North Korea and Laos. Are there any others? Socialism for China is like Shiite Islam for Iran. But what does Socialism mean, apart from one-party-rule? I think it’s something to believe in, and to practice, to change the fates of working people through actions of solidarity. Isn’t that what the New Citizen movement was trying to do? But Xu has all but dismissed Socialism and has not tried to invoke it as something originally worth believing in. This is understandable, under the circumstances. But can you imagine someone standing up in court in Iran and asking “Can you explain what Islam entails?” Maybe people do it, I don’t know. They probably wouldn’t dismiss religion.

Actually, it is more complicated. I think Xu is testing what is possible. how far the system will go to crush opposition. In his obstinacy he could be compared to Shi Mingde (Shih Ming-te) 施明德 in Taiwan in the 1980s. But Xu is much younger than Shi was in the late 1980s, he was only 15 in 1989.

“Me: Aren’t the communist party and socialism western products? May I ask, what is socialism? If a market economy is socialist, why is democracy and the rule of law, which we are pursuing, not socialist? Does socialism necessarily exclude democracy and the rule of law?”

C:你的一系列文章,比如《人民的国家》,整个照搬西方体制,反党反社会主义,你们的组织活动,几个月发展到几千人,你的行为已经构成犯罪,而且不止一个罪名。

我:共产党、社会主义难道不是西方的吗?请问什么是社会主义?市场经济如果是社会主义,我们追求的民主法治为什么就不是社会主义?社会主义必然和民主法治对立吗?关于反党,这个概念太极端,方针政策对的就支持,错误的就反对,而且,我对任何人都心怀善意,如果共产党经过大选继续执政,我支持。[…] 我可能比你更爱中国!你有空可以看看我写的《回到中国去》,看一个中国人在美国的经历和感想。而你们,多少贪官污吏把财产转移到了国外?

C:爱党,爱国,爱人民,三位一体,你不爱党,怎么爱国爱人民?

我:我的祖国五千年了,来自西方的党还不到百年,将来共产党不会千秋万世永远统治,怎么可能三位一体?我爱中国,我爱13亿同胞,但我不爱党。一个原因是历史上它给我的祖国带来的太残酷的伤害,数千万人饿死,文化大革命彻底摧残了中华民族的精神文化,还有就是今天这个党太肮脏,大量贪官污吏,从申请书到入党宣誓都是在公然撒谎——有几个真的要为共产主义奋斗终身?我厌恶谎言,我厌恶为了私欲不择手段,我厌恶一个人在宣誓的时刻也撒谎。

C:敢说不爱党,算你是好汉。考虑到你的主张自由、公义、爱还不错,目的是好的,本着教育的方针,还是希望爱党,放弃公民活动,多和社会各界接触,看问题更客观些。

我:谢谢提醒,我会努力更加客观理性,既看社会问题,也看新闻联播。具体活动如果有不当之处,我可以听取建议,有些行为如果超前了,可以停下来,都可以协商,但是别说什么犯罪。

C:我知道一时半会改变不了你的观点。看过你的档案,你这个人多年来就像一根针一样那么恒定,立场就在那里一动不动。下次接着谈吧。明天后天下午什么时候你觉得合适?

我:明天吧。[words marked by me, see below]

This dialogue between Xu and Beijing State Security official C is very interesting. There is a measure of mutual respect. Xu has spunk, he is brave and obstinate. He mentions “数千万人饿死”, tens of millions died of hunger, as one of the main reasons for not “loving the party” 爱党, as suggested by his interrogator. This dialogue should be very good material for studying Chinese. This section is from the end of the first day (June 25) of Xu’s interrogations in June 2013. You can compare the original to the translation on http://Chinachange.org. In the translation, I could not access the link to Xu’s patriotic article Go Back To China 《回到中国去》, written in New York a few years ago, but it seems to be available on several blogs readily accessible in China.

‘I Don’t Want You to Give Up’ – a public letter by Xu Zhiyong’s wife.

Words like “citizen” and “love”, and any other words or means of expressions, actually, become something remarkably different in a work of art, different from every-day-usage, and usage in political statements. I find Xu’s use of “love” baffling. “Love” strikes me as rather imprecise, compared to “justice”, for example. Love, simply love, not compassion or caritas. Not bo’ai 博爱, just aì 愛, as in Wo ai ni 我愛你。Imprecise, but endearing, as something obviously non-political. And thus closer to poetry, literature, art? Ubi caritas et amor, deus ibi est. All You Need is Love. And so on.

“If I had a hammer I’d hammer in the morning/ I’d hammer in the evening all over this land/ I’d hammer out danger, I’d hammer out warning/ I’d hammer out love between my brothers and my sisters/ All over this land …” Pete Seeger (May 3, 1919 – January 27, 2014)

The International Federation of Journalists has issued a report on press freedom in China in 2013. Here are two small excerpts:

“On May 3, a woman named Yuan Liya was found dead

outside Jingwen shopping centre in Beijing. Police said

Yuan had jumped from the shopping centre, but her

parents suspected she was killed after she was raped

by several security guards during the night. On May

8 the media was instructed to republish a statement

issued by the Beijing Police and further ordered that

no information could be gathered from independent

sources. All online news sites were told to downplay the

case and social microblogs were required to remove all

related news items.”

This immediately reminds me of SHENG XUE’s 盛雪 poem YOUR RED LIPS, A WORDLESS HOLE, from early 2007. The original is titled NI KONGDONG WU SHENG DE YU YAN HONG CHUN 你空洞无声的欲言红唇. The poem was translated into German by Angelika Burgsteiner and recited in early March 2013 at TIME TO SAY NO, the PEN Austria event for International Women’s Day, in cooperation with PEN Brazil.

“On May 14, media outlets disclosed that several

primary school principals were involved in scandals

involving sexual exploitation of minors. All of the alleged

victims were primary school students. Some bloggers

initiated a campaign aimed at protecting children, but

the authorities demanded that the media downplay

both the scandal and the campaign.”

Cf. Lily’s Story 丽丽传 by Zhao Siyun 赵思云, from 2012.

In China, a Young Feminist Battles Sexual Violence Step by Step

标签:art, concepts, 许志永, freedom of speech, horse, internet, justice, law, new year, poetry, politics, rights, speech, spring, trial, women, words, workers, Xu Zhiyong, Yan Li, 概念

发表在 January 2014, Translations, Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »